From 1936 to 1970, San Francisco’s Chinese nightclubs were the epitome of Hollywood glamour — with a Bay Area twist: All of the performers were Asian American.

The floor acts ranged from Frank Sinatra-style crooning and elegant ballroom dancing to breathtaking acrobats and titillating burlesque stripteases. Some performances leaned on American stereotypes of Chinese culture, while others embraced All-American Las Vegas-style razzle-dazzle, shocking the mostly white audiences.

Coby Yee, who died on Aug. 14 at age 93, was one of the last headline-grabbing stars of Chinatown. Originally from Columbus, Ohio, she began her career after World War II, dancing through the Chinatown nightclub circuit, which included The Lion’s Den, the Chinese Sky Room, Kubla Khan, Li Po Lounge, Club Mandalay, Chinese Palace, the Dragon’s Lair and Club Shanghai. By the late 1940s, Lee was touring the country as part of the Chinatown Follies troupe, and eventually, she would perform in Vegas.

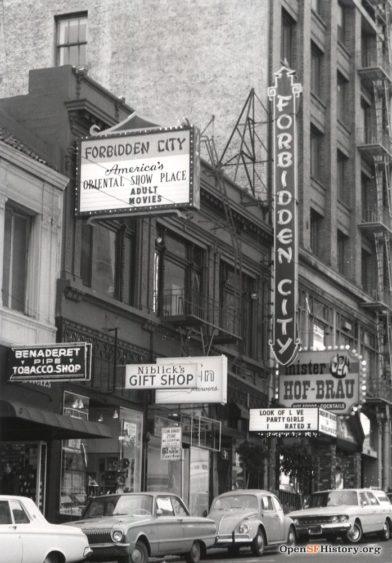

The biggest San Francisco club Yee danced at was Forbidden City, located two blocks outside Chinatown on Sutter Street. By the late 1950s, Yee became Forbidden City’s star attraction, billed as “China’s Most Daring Dancing Doll.” She was known for her stunning stripteases, which she performed three times a night, where she slowly removed the ornate costumes that she designed and sewed herself.

Born on Nov. 2, 1926, Yee grew up in Columbus, Ohio, and her parents, Chinese immigrants, made the unusual choice to enroll her in tap dance classes when she was just 6 years old.

Yee’s nephew, Darrell Leong, explained in author and historian Trina Robbins’ 2010 book, “Forbidden City: The Golden Age of Chinese Nightclubs,” that most of the showgirls in the Forbidden City chorus were brought up by traditional Chinese families who thought American dance classes were frivolous. So unlike Yee, these young women only started to learn the footwork after the club had hired them.

A towering figure who was only 4 feet 11 inches, Yee started performing on the Chinatown circuit because she loved dancing and showbiz, but her economic circumstances put her in a position where she felt she had to compromise her modesty.

In “Forbidden City,” a collection of photos and interviews about Chinatown nightlife that Robbins put together, Leong elaborated:

“She was a legitimate dancer, a little tap dancing, ballet.”

Tweet this!

Leong added:

“When she came to San Francisco, they said ‘Hey, you could make $50 more if you took this off.’ It was never her intention to be an exotic dancer; it’s really an economic choice. … [So] what she did cleverly was to add more layers. … She would insist that every time a piece of garment would come off, the spotlight would grow darker and darker and darker. A tease, right? So she never really was comfortable with the term ‘stripper.’ It became euphemistically called ‘exotic dancer.'”

Tweet this!

Yee also turned her ability to make flashy and cleverly layered costumes into a lucrative operation.

Yee told Robbins:

“I kinda fell into [costume designing] because I performed in Las Vegas. That’s when I realized that some of the showgirls really needed wardrobes, so I always took my sewing machine with me. So before I knew it, I was doing big business making costumes.”

Tweet this!

By her early 30s, Yee was also directing and producing revues and managing her own clubs.

In December 1959, she, her then-husband, Jimmy Yee, and a business partner named Emma Chan opened a jazz club, The Dragon Lady, on Broadway in San Francisco. Then, in December 1962, the Yees bought Forbidden City and renamed it Coby Yee’s Forbidden City.

Unfortunately for the Yees, and the dozen or so extended family members who worked at the supper club, Yee and her pasties were about to be upstaged by Carol Doda, who shocked the country with her topless performance in June 1964 at the Condor Club in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood. The Yee family finally had to shut down Forbidden City in 1970.

A Nevada-born Chinese American entrepreneur named Charlie Low opened Forbidden City on Dec. 22, 1938. It was the second Chinese supper club to open in the city, a year after the Chinese Sky Room.

Low’s club offered inexpensive American-style Chinese cuisine like chow mein and promised an “all-Chinese” floor show that included a live band, bawdy comedians, acrobats, sophisticated singers and a high-kicking chorus

In Arthur Dong’s 1989 documentary film, “Forbidden City, USA,” remastered in 2015, club secretary Lenna Chan declared:

“It was like a three-ring circus every day – no kidding!”

Tweet this!

Low — who eventually grew rich enough to buy a 72-acre ranch in Pleasanton, complete with horses and a swimming pool — worked the room every show, making each guest feel as if they were his best friend.

Despite the theatrics and Low’s easy charm, Forbidden City struggled to draw patrons until 1940, when it introduced the “Chinese Sally Rand,” a UC Berkeley student called Noel Toy, whose act involved prancing around the dance floor mostly nude, holding a large opaque balloon or two giant feather fans that covered her body. Lurid curiosity about the bodies of cute, young Asian American women piqued the interest of white Americans looking for a night on the town.

Later that year, Life magazine published a three-page spread titled “Life Goes to the ‘Forbidden City’: San Franciscans pack Chinatown’s No. 1 night club,” and then the club really blew up, attracting a couple thousand patrons a day and more journalists from magazines and newspapers around the country.

At that moment in time, as Europe went to war, the United States was just coming out of the Great Depression. For the first time in a decade, Americans had money to spend on live entertainment. From the late 1920s through the ’30s, the cinema had been a cheap form of escapism, as U.S. audiences dreamed about the luxurious lives of the sophisticated Golden Age starlets and singers in their posh evening gowns and tuxedos.

By the late ’30s, sound film was reaching its artistic peak, and now that regular folk could afford to go out, they wanted to experience some of that glitz in person.

San Francisco’s Chinese nightclubs promised Hollywood-like glamour — and often stars like Bob Hope, Gene Kelly, Rita Hayworth, Duke Ellington and Bing Crosby would make an appearance at spots like Forbidden City — with a bit of erotic titillation, such as leg-flashing showgirls, and the added novelty that the legs belonged to purportedly modest Chinese American women.

In “Forbidden City, USA,” club pianist Fritz Jensen and longtime San Francisco tour guide Bill Nowak explained that Forbidden City’s location, just outside of Chinatown, was a key to its success. The white clubgoers who made up the bulk of the audience were intrigued by pretty Chinese performers in the posters, but expressed racist fears of walking through the all-Chinese American neighborhood where similar nightclubs dotted Grant Avenue.

In 1940, San Francisco had one of the largest urban Chinese American populations in the U.S., accounting for 4.2 percent of the city’s residents, whereas across the country, Chinese Americans only made up 0.2 percent of the population.

The tight-knit Chinese community in San Francisco generally frowned on the racy “modern” revues that took place in these new nightclubs.

Gladys Hu, a former Forbidden City patron who grew up in San Francisco’s Chinatown, explained in “Forbidden City, USA.”:

“It was quite a scandalous place to be going because you had showgirls who were only partly dressed — I mean with skimpy costumes and so on.”

Tweet this!

For that reason, most of the Asian American entertainers in San Francisco — who were Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Filipino, but billed as “all Chinese” — came from other towns and states, so their parents and grandparents were too far away to be scandalized by their acts.

Performing at the Forbidden City and other San Francisco nightclubs in the ’30s and early ’40s was an act of rebellion for these young people who wanted to chase their Hollywood dreams. Many of them first tried to make it in Los Angeles, but were shut down by racist studio execs.

Trina Robbins, who is also an esteemed comic book artist and writer, met several elderly Chinatown entertainers while taking a dance class in the late 2000s.

In a 2014 interview for Collectors Weekly, Robbins said:

“In some cases, these performers might not have had mothers who had bound feet, but they at least had grandmothers who did.”

Tweet this!

Robbins added:

“But this was the new generation that grew up in America: They ate hamburgers, and they Charlestoned. They saw Chinese American silent film star Anna May Wong in the movies. If Anna May Wong could perform, why couldn’t they? They wanted to dance. They wanted to sing. It was their talent. In many cases, the women, especially because their parents disapproved, had to run away from home to dance.”

Tweet this!

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, servicemen from all branches of the armed services were stationed in San Francisco before being deployed to fight the Japanese military in the Pacific theater of World War II.

Many young men coming into San Francisco from the Midwest and South had never seen an Asian American person in their lives, and were eager to experience the famous San Francisco Chinatown scene and flirt with the “China dolls.”

Performers who were ethnically Japanese, like dancer Dorothy Toy, had to flee or stay away from the West Coast in early 1942 to avoid being locked up in internment camps.

After the war, Chinatown’s once-booming nightclubs began to struggle, thanks, in part, to the federal cabaret tax of 1944. But also, according to “Forbidden City, USA,” the returning soldiers were focused on getting married and settling down, as opposed to meeting cute girls at nightclubs, and their new families started to obsess over a new in-home form of entertainment — television. By 1954, more than half of all U.S. homes had a TV, and by 1962, 90 percent did.

Despite cultural shifts, the biggest Chinese nightclubs, like Forbidden City and Chinese Sky Room, stayed afloat through the 1950s and ’60s. The romantic fascination with Forbidden City was strong enough to inspire C.Y. Lee’s bestselling 1957 novel “Flower Drum Song”, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s hit 1958 Broadway musical of the same name and the less-than-successful 1961 film adaptation of the musical.

Yee, who’d come up as a dancer after the war, was regularly mentioned in the San Francisco Examiner’s gossip and entertainment columns in the late 1950s and early ’60s, by white male columnists who didn’t hide their lascivious interest in her work. Yee also attracted royalty: In her San Francisco Chronicle obituary, Sam Whiting explains that Belgium’s Bachelor King Baudouin made a point to see her act in 1959.

In the book, “Forbidden City,” Candice Ponciano — one of Yee’s employees in the ’60s, a dancer who followed in the footsteps of her mother Ellen Chinn — told Robbins:

“She was a nice lady, petite, great figure, and a great hostess at her club, and glamorous, always dressed perfectly.”

Tweet this!

Ponciano continued emphatically:

“You would never catch her in a sweatsuit.”

Tweet this!

When Coby and Jimmy Yee took over Forbidden City in 1962, they put the whole family to work, from washing dishes to sewing costumes.

Yee told Robbins:

“It’s a family operation. We were all there and we were trying to pitch in. … Some of them were cooks, some of them were bartenders, some of the kids were waiters, I happened to be a dancer. That was my job. I have a brother who sang; the other one was a pianist. The whole family [made the costumes]. There were all types. Every 6 weeks we changed shows.”

Tweet this!

She also told Robbins she had opportunities to make more money dancing in Vegas or on tours to far-flung locales like Hong Kong and Australia, but her obligations to her family-run business mostly grounded her in San Francisco, where she feverishly churned out costumes and rehearsed her performers.

During the mid-1960s, the Forbidden City family’s teenage children, including Coby Yee’s daughter with her previous husband, Charmaine “Shari” Yee Roh, and her nephews Darrell and Dennis Leong, were enlisted to perform cute song-and-dance acts. At that point in history — the Vietnam era with the rise of rock ‘n’ roll, topless dancing and San Francisco Bohemians — the rhinestone-and-sequin-studded cabaret and burlesque performances were becoming hopelessly passe and corny. The tourists that frequented Gray Line Tours, which used to drop clients off at Forbidden City by the busloads, lost interest.

Darrell Leong told Robbins:

“During the [World War II], the uniqueness of Asian women baring their legs to essentially a non-Asian clientele, the concept was quite revolutionary … but it wasn’t certainly subversive in the ’60s and ’70s.”

Tweet this!

By 1980, Yee had settled down in San Pablo, and turned her focus to her seamstress business and teaching dance on the side. In the mid-2010s, Yee joined up with several other former Chinatown entertainers as part of the Grant Avenue Follies, a vintage-Chinatown-style performance troupe, which was founded by Cynthia Yee in 2004 and now includes a poet, a magician, a singer and nine dancers.

Cynthia Yee, unrelated to Coby, danced at Andy Wong’s Chinese Sky Room in the 1960s and was crowned Miss Chinatown 1967 — she didn’t really become close with Coby until she joined the Follies. To Hoodline’s Nikki Collister, Cynthia described Yee as “a ball of fire” during a 2018 trip to Cuba. The 91-year-old “would go out dancing after midnight, while the rest of us were ready to go to bed.”

She hadn’t slowed down at all by September of last year, when the Grant Avenue Follies performed at the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai. Cynthia Yee told the Chronicle, Coby “was ready to go disco dancing after the show.”

Coby Yee also danced and taught headdress-making at the Firecracker Revue at the Clarion Performing Arts Center in San Francisco in February of this year.

In May, the Burlesque Hall of Fame Museum in Las Vegas announced that Coby Yee would be the recipient of the 2020 Living Legend Award, for her trailblazing work during the heyday of burlesque. Yee received her award in a video recorded on July 25, but she passed away two weeks before the official online broadcast of the Hall of Fame’s Weekender ceremonies, which took place last month.

In the video, the ever-charming Yee accepts her trophy outside her San Pablo home, wearing a headdress and a bright gown of her own design — with her trademark leg-revealing side slits. Before she performed with her longtime partner in life and dance, Stephen King, she declared the pandemic wasn’t holding her back, and the two demonstrated how “we dance in our driveway.”

Yee’s romance with King, an experimental filmmaker 20 years her junior, is highlighted in the 2019 short documentary film, “Coby & Stephen Are in Love,” directed by Carlo Nasisse and Luka Yuanyuan Yang, which was featured at the 2020 Big Sky Documentary Film Festival.

King is seen meticulously archiving and making collages out of Yee’s photos. He said:

“Of course I don’t want to be forgotten, but I really don’t want her to be forgotten.”

Tweet this!

To read about San Francisco glamorous Chinatown nightlife, pick up Dong’s 2014 book “Forbidden City, USA: Chinatown Nightclubs, 1936-1970,” and Trina Robbins’ 2010 book “Forbidden City: The Golden Age of Chinese Nightclubs.”

Robbins, who was profiled for SF Senior Beat in June 2020, has a new book out, “The Flapper Queens: Women Cartoonists Of The Jazz Age.”

To see original midcentury Chinatown entertainers perform, check out the Grant Avenue Follies.

This story was first published on LocalNewsMatters.org, an affiliated nonprofit site supported by Bay City News Foundation.

Bay City News is a 24/7 news service covering the greater Bay Area. © 2022 Bay City News, Inc. All rights reserved. Republication, rebroadcast or redistribution without the express written consent of Bay City News, Inc. is prohibited.